A CONSISTENT MARKET PHENOMENON

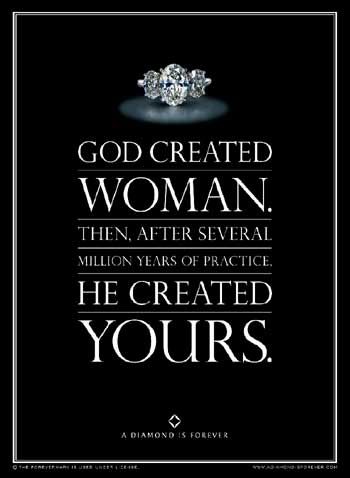

The association of the diamond with love and marriage was a strategic master-stroke, for it cemented the diamond’s status as a consistent market phenomenon, which is a rare commodity in the luxury arena. Although marriage rates rise and fall, the concept never really goes out of fashion, meaning that bridal jewelry has remained a fixture, decade after decade. Furthermore, since get married all through the year, the business is not seasonal.

Furthermore, despite their value, unlike cars and houses most diamonds are sold only once. Bridal jewelry, which is associated with one of the most emotionally charged moments in a person’s life, rarely enters the resale market. It is more likely to be handed down from generation to generation.