- About MID

- Search Diamonds

- White Diamonds

- Fancy Colored Diamonds

- Loose Diamonds

- shows

You are cordially invited to join us at Gemgenevé Show 2024: Boot: D-30.

M.I.D. Specializes in: All shapes and sizes from 0.30ct to extreme sized diamonds of 10.00+ct; Parcels, single stones, matched pairs, and layouts Certified stock from GIA, EGL, AGS, HRD, and IGI Extremely Rare Fancy Colored Specialty Stones Premium cuts to value cuts in all shapes Fancy colored diamonds available in one-of-a-kind jewelry.

ABOUT THE HONG KONG JWEWLLERY AND GEM FAIR

The Hong Kong Jewellery & Gem Fair is considered is amongst Asia’s top 3 fine jewellery events and is a must attend trading event. In June 2019 31st Hong Kong Jewellery & Gem Fair will take place at the Hong Kong convention and exhibition center and host 2,300 exhibitors from over 40 countries around the world.

MID House of Diamonds will be present and exhibiting at the September 2023 Hong Kong Jewellery & Gem Fair. Join Us! Booth: D 30

more trade shows

Play VideoPlay VideoPlay VideoPlay VideoGLIMPSE FROM our trade SHOWs…

Play VideoJCK 2019 LAS VEGAS SHOW

MID House of Diamonds will be among the exhibitors at the June 2020 JCK Vegas Show. Come say Hi!

Play VideoHK SEPTEMBER SHOW

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet conse ctetur adipisicing elit.

Play VideoHK NOV SHOW

Ipsum dolor sit amet conse ctetur adipisicing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt.

Play VideoHK MARCH SHOW

Dolor sit amet conse ctetur adipisicing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor.

- BLOG

FROM OUR BLOG

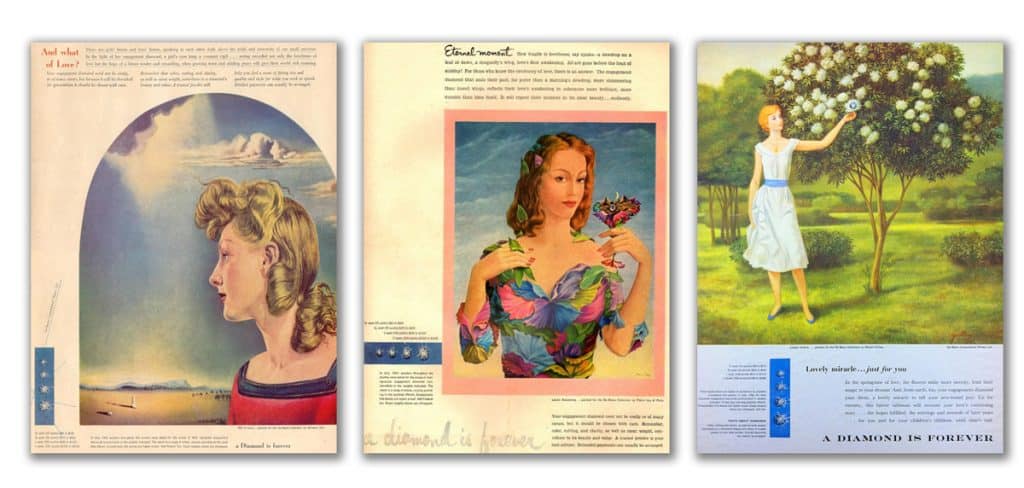

INVITATION-ONLY CENTURION SHOW IN PHOENIX SET TO OPEN ARIZONA’S ANNUAL GEM SHOW FORTNIGHTAs it does it each year, through the end of January and the first two weeks of February the Arizona desert will attract gemstone and jewelry buyers from around the world. They are drawn into the western U.S. state not only by the generally sunny winter weather, but also by a series of trade shows, ranging from high-end events to displays literally arranged on the backs of trucks.RECENT

BOTSWANA TAKING STAKE IN ANTWERP DIAMOND COMPANY, COULD PROVIDE STRATEGIC ALTERNATIVE TO DE BEERS

The government of Botswana has announced its intention to take a 24 percent stake in a Belgian-headquartered diamond company, HB…FOCUS

AS BOTSWANA’S SALES AGREEMENT WITH DE BEERS SET TO EXPIRE, COUNTRY’S PRESIDENT SUGGESTS ALL OPTIONS ARE ON TABLE

Sometime during the coming few weeks or months, the government of Botswana and De Beers are expected to announce a…WORLD’S MOST VIVID PINK DIAMOND TO GO ON BLOCK, COULD BRING IN $35 MILLION OR MORE

Weighing 10.57 carats and called the Eternal Pink, the stone is estimated to be worth more than $35 million. It… - resources

- ContactAddress:

580 5th Ave #3003, New York, NY 10036

Phone:+1-212-391-1121

Free:+1-877-391-1121

E-mail: